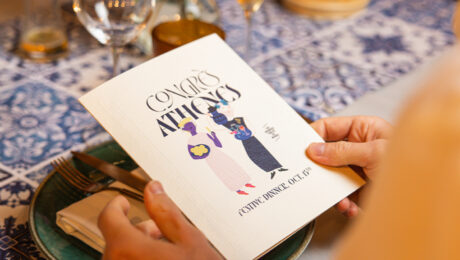

CAMILLE DE CUSSAC, THE COLORS OF OUR CONGRESS

A look back at our congress in Athens, for which we were fortunate and delighted to be accompanied by the great illustrator Camille de Cussac. Thanks to her remarkable talent, singular style, vivid colors and delicate sense of humor, she infused this edition with an energy that was as festive as it was sunny - in her own image.